Chapter 5: Statement of Significance

This chapter is largely derived from other official sources. It describes the elements of natural beauty that are important to this landscape.

This chapter is largely derived from other official sources. It describes the elements of natural beauty that are important to this landscape.

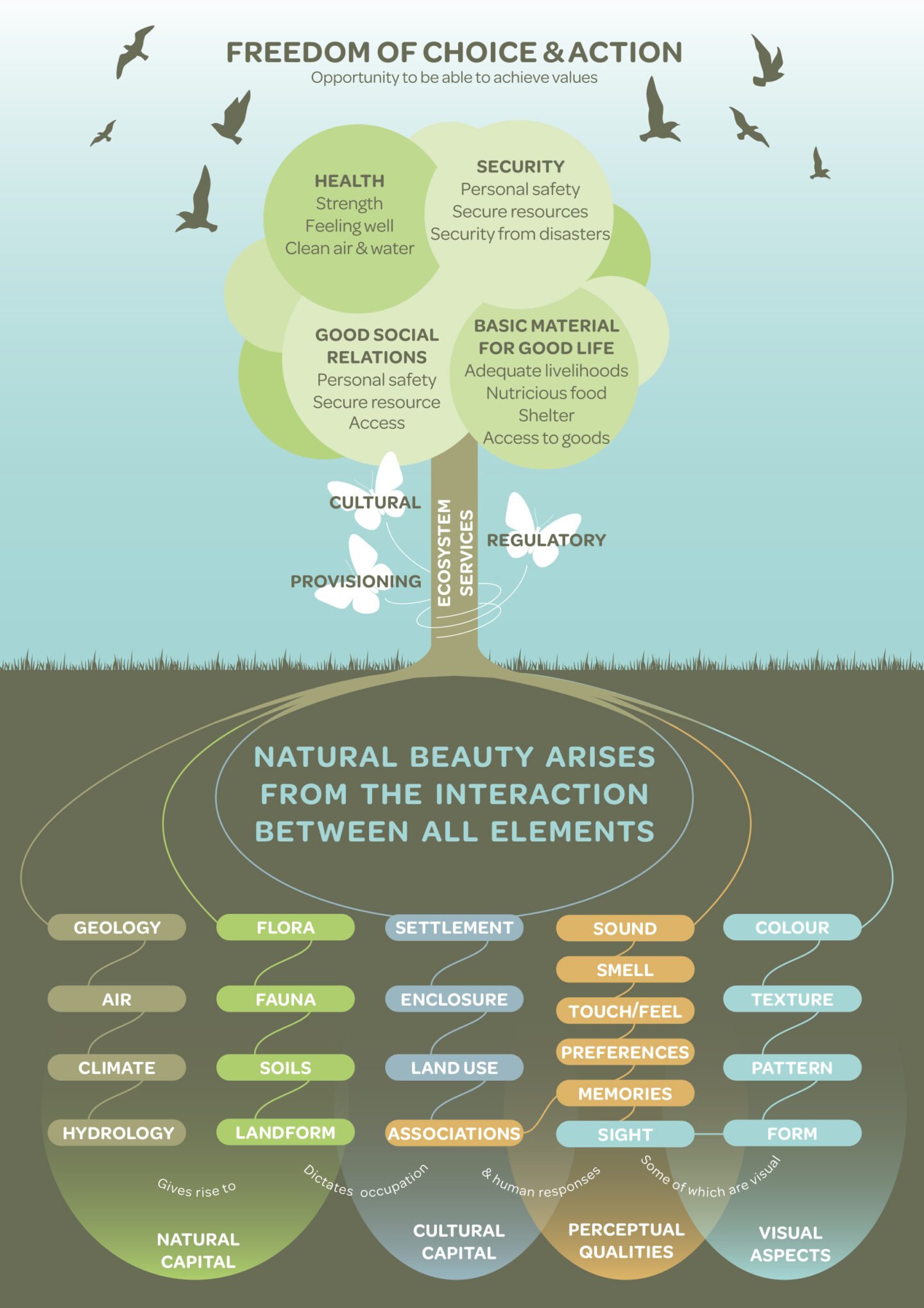

National Landscapes are designated for their outstanding natural beauty. Natural beauty goes beyond the visual appearance of the landscape, including flora, fauna, geological and physiographical features, manmade, historic and cultural associations and our sensory perceptions of it. The combination of these factors in each area gives a unique sense of place and helps underpin our quality of life.

The natural beauty of this National Landscape is described in a suite of special qualities or properties that together make it unique and outstanding, underpinning its designation as a nationally important protected landscape. These are the elements we need to conserve and enhance for the future and they should be considered in all decisions affecting the National Landscape. This Statement of Significance is based on the 1993 Assessment of the Dorset National Landscape produced by the Countryside Commission. The special qualities of the Dorset National Landscape are:

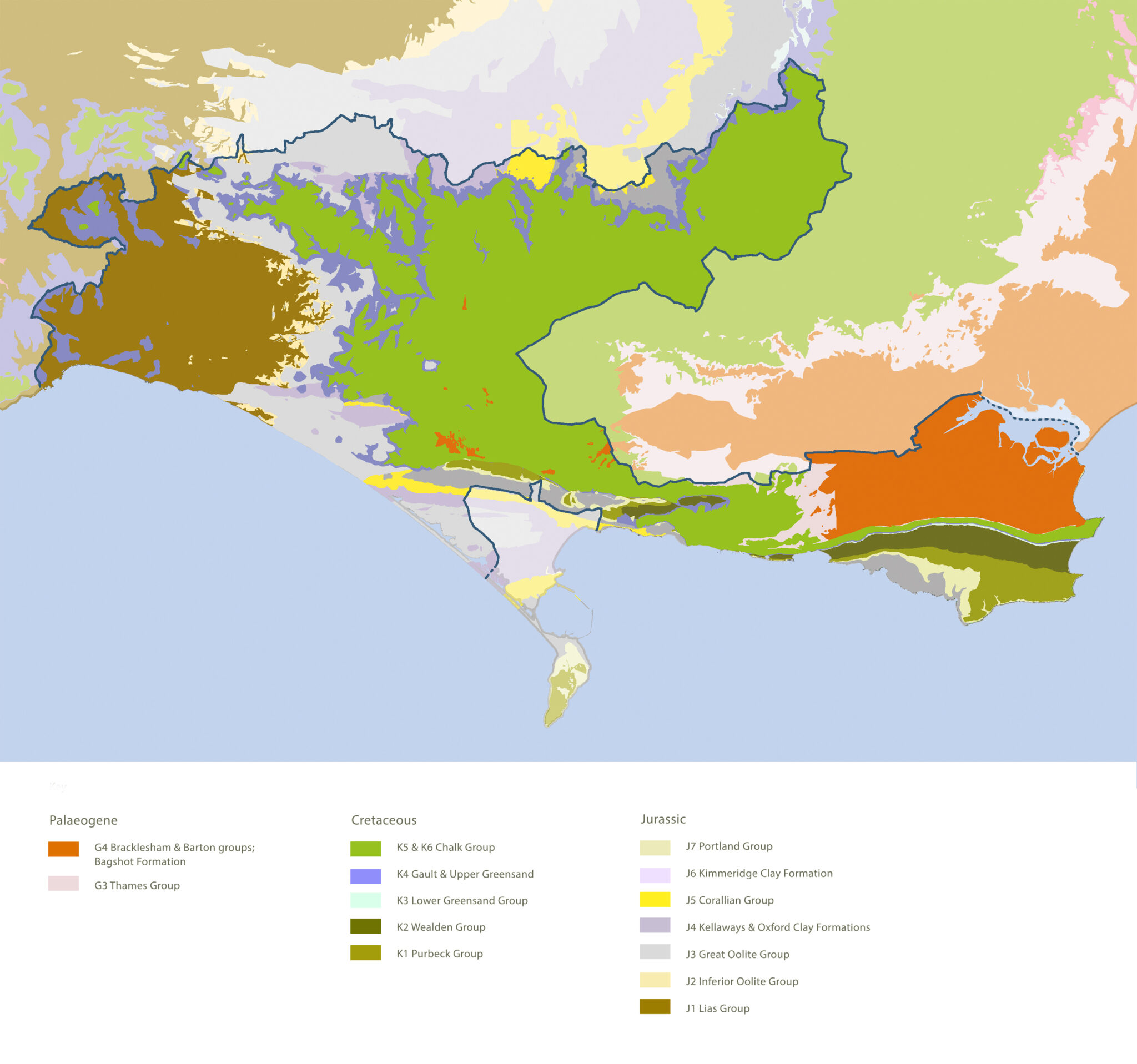

The National Landscape is much more than one fine landscape – it is a collection of fine landscapes, each with its own characteristics and sense of place, including different landforms, soils and wildlife habitats. Contrasting and complex geology gives rise to the chalk downland, limestone country, heathlands, greensand ridges and clay vales that occur in the Dorset National Landscape; they are often closely juxtaposed to create striking sequences of beautiful countryside that are unique in Britain. The transitions between the component landscapes of the mosaic are often particularly attractive, with strong contrasts in some areas and a gentle transition of character in others.

The ridge tops and chalk escarpments add an extra dimension to the Dorset National Landscape by providing stark contrasts of landform that serve to increase and emphasise its diversity. These areas of higher ground also allow the observer uninterrupted panoramic views to appreciate the complex pattern and textures of the surrounding landscapes.

Nowhere is the contrast and diversity of this rich assemblage of landscapes more graphically illustrated than in the Isle of Purbeck. Here, many of the characteristic landscapes of the Dorset National Landscape are represented on a miniature scale to create scenery of spectacular beauty and contrasts, which mirrors that of the whole area.

Within this overall context, there are numerous individual landmarks, such as hilltop earthworks, monuments and tree clumps that help to contribute an individuality and sense of place at a local scale.

In addition to its outstanding scenic qualities, the National Landscape retains a sense of tranquillity and remoteness that is an integral part of these landscapes. It retains dark night skies and an undeveloped rural character. The National Landscape’s Landscape Character Assessment, ‘Conserving Character’, adds further understanding of the contrast and diversity of the area’s landscapes and their management requirements.

The area’s diverse landform and striking changes in topography are dictated by the National Landscape’s varied geology, upon which subsequent erosion has occurred. This ‘land-shape’ has then been inhabited, built upon and in some places modified by several thousand years of population.

Landscape is a framework which encompasses geological, hydrological, biological, anthropological and perceptual qualities. The Dorset National Landscape’s Landscape Character Assessment describes these features and qualities in more detail, by subdividing the area into character types and character areas.

Running throughout each character area are qualities that make the National Landscape inspiring and special, such as the sense of tranquillity and remoteness and sweeping views across diverse landscapes. The variety of landscape types found within the area is a defining feature of the National Landscape underpinned by diverse geology, with dramatic changes from high chalk and greensand ridges to low undulating vales or open heaths. It is often the transition from one landscape type to another that creates drama and scenic quality. At the local level, individual landmark features and boundaries add to character.

Under this aspect of the National Landscape’s special qualities and natural beauty, however, the main consideration is for the characteristics and qualities of the landscape, such as the undeveloped rural character, tranquillity and remoteness, dark night skies and panoramic views. Through the main modes of interaction with the place, this plan considers some of the broad issues that can affect them. Landscape character and condition are more fully described in Chapter 6.

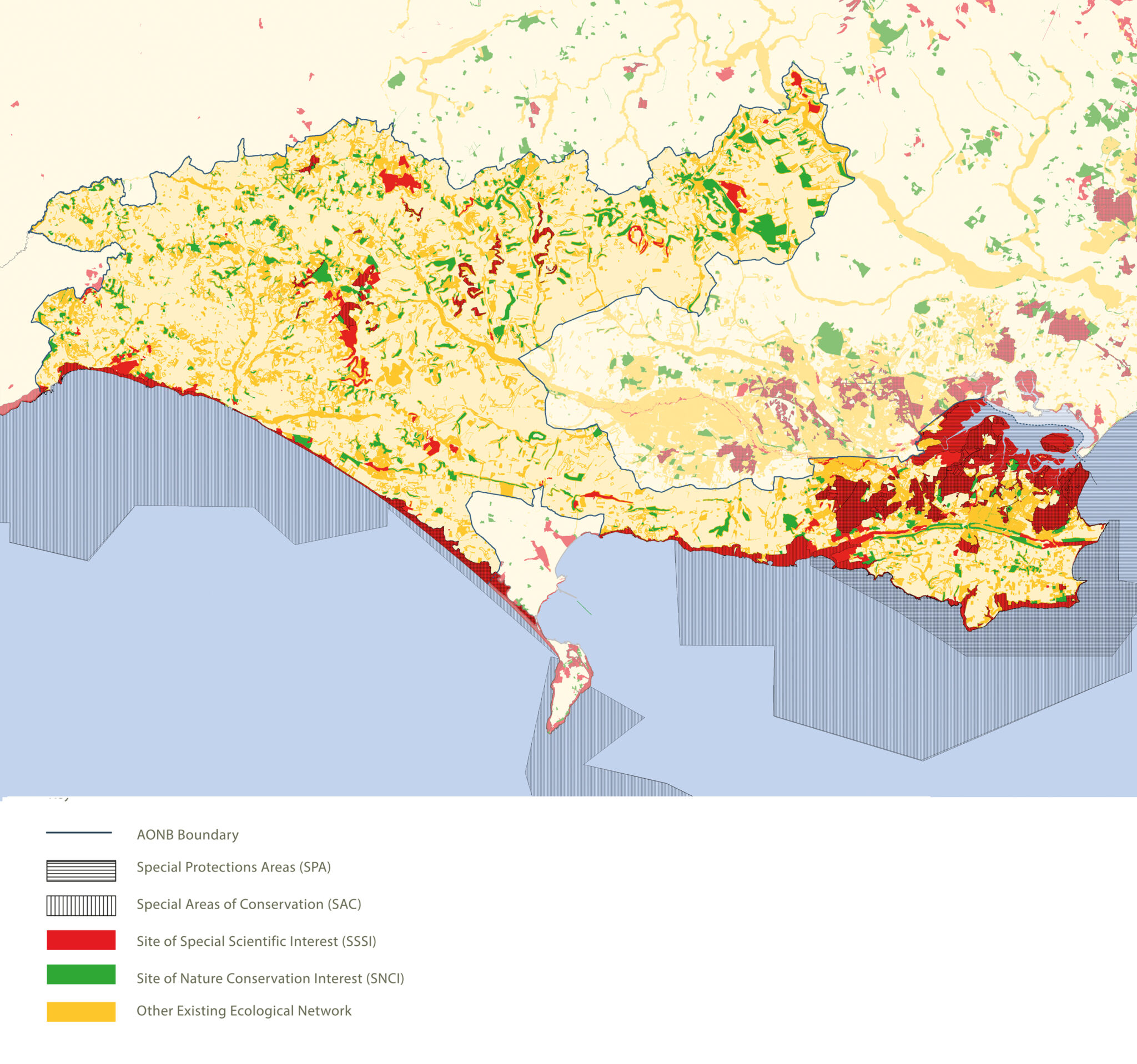

The contrast and diversity of the National Landscape is reflected in its wildlife. The range of habitats and associated species is unusually rich, including 83% of all British mammal species, 48% of bird species and 70% of butterfly species. The UK’s richest grid squares for vascular plants and mammals are both found in the Dorset National Landscape. The National Landscape’s southern location and relatively warm climate make it hospitable to many species unable to survive further north and home to species new to Britain, naturally expanding their ranges with the changing climate. The National Landscape includes many areas of international significance, including Poole Harbour and the Fleet which are key sites for breeding and overwintering birds, lowland heath areas in the east, calcareous grasslands in the Cerne and Sydling Valleys and Purbeck Coast, ancient woodlands at Bracketts Coppice and the West Dorset alder woods, and important cliff and maritime habitats along significant sections of the coast.

Two marine SACs are adjacent to significant lengths of the National Landscape’s coastline; there are two candidate marine SPAs and three Marine Conservation zones adjacent to the National Landscape boundary. Further coastal and marine areas are proposed for protection.

Many other areas are important at the national level and are supported by a large number of locally significant sites.

The quality of the wider National Landscape offers high potential to rebuild extensive mosaics of wildlife habitat and to improve the linkages between them.

Biodiversity is the variety of all life on Earth. It includes all species of animals and plants, and the natural systems that support them. Biodiversity matters because it supports the vital services we get from the natural environment. It contributes to our economy, our health and wellbeing and it enriches our lives. Dorset has an exceptional wealth of biodiversity and this plan addresses the issues and opportunities for the species, habitats and natural systems in the Dorset National Landscape. There has been a long history of partnership working to deliver biodiversity conservation in the county, and this plan seeks to complement this.

Biodiversity is a fundamental element of natural beauty. The National Landscape’s wealth of wildlife, from the common and widespread to the globally rare, is one of the outstanding qualities that underpin its designation. The biodiversity of the National Landscape is shaped by the underlying geology and its influence on soils and hydrology. It is also influenced by the social, cultural and economic activities of past and present land use, which biodiversity supports by providing resources such as food, timber, clean water and crop pollination amongst others. Biodiversity also provides us with opportunities for recreation, relaxation and inspiration and a range of associated tourism opportunities. Dorset is particularly rich in some habitats and species. For example, lowland heathland and the characteristic species associated with it form a recognisable landscape across southern England, but in Dorset there is a concentration of species such as sand lizards and smooth snakes that do not occur in such numbers anywhere else in the country. The same could be said of the coastal habitats of Poole Harbour and the Fleet within the boundary and the marine SACs on its southern boundary. Since 1945, the landscape has changed markedly in response to changes in economic, agricultural and forestry policies. For example, some of our most cherished wildlife areas have become degraded over time through habitat loss and fragmentation associated with agricultural intensification, conifer afforestation and increasing development pressures. Current and future pressures and competing land uses will continue to have impacts, including agricultural policy, climate change, invasive species (new pests and diseases). A step-change in our approach to nature conservation is required to ensure that natural systems are repaired and rebuilt, creating a more resilient natural environment for the benefit of wildlife and ourselves. The Local Nature Recovery Strategy will guide this step change, in conjunction with local data on functioning ecological networks and habitat restoration opportunities.

The Dorset National Landscape encompasses a breadth of biodiversity – chalk and limestone grassland which is found across the National Landscape and along the coast; lowland heathland concentrated in the eastern part of the National Landscape; ancient meadows and woodlands scattered throughout; the coastal habitats of Poole Harbour and the Fleet; and maritime coast and cliff along much of the Jurassic Coast. This is reflected through a number of nature conservation designations:

• Three Ramsar Sites; wetlands of global importance: Chesil Beach and the Fleet, Poole Harbour, and Dorset Heathlands. In total they cover 5.1% of the National Landscape.

• Thirteen Special Areas of Conservation (SACs) of international importance for habitats and species within or directly adjacent: Bracket’s Coppice; Cerne and Sydling Downs; Chesil and the Fleet; Crookhill Brick Pit; Dorset Heaths; Dorset Heaths (Purbeck and Wareham) and Studland Dunes; Isle of Portland to Studland Cliffs; Lyme Bay and Torbay; River Axe; Sidmouth to West Bay; St. Aldhelm’s Head to Durlston Head; Studland to Portland; and West Dorset Alder Woods. In total they cover 5.8% of the National Landscape.

• Four Special Protection Areas (SPAs) of international importance for birds: Chesil Beach and the Fleet; Dorset Heathlands; Poole Harbour; and Solant and Dorset Coast. In total they cover 6.2% of the National Landscape. Together, SACs and SPAs form a network of ‘Natura 2000’ sites – European sites of the highest value for rare, endangered or vulnerable habitats and species.

• Three Marine Conservation Zones, protected for nationally important marine wildlife, habitats, geology, and geomorphology: Studland Bay; Purbeck Coast; and Chesil Beach and Stennis Ledges.

• Ten National Nature Reserves (NNRs) lie wholly or partly within the National Landscape: Arne Reedbeds; Axemouth to Lyme Regis Undercliffs; Durlston; Hambledon Hill; Hog Cliff; Holton Heath; Horn Park Quarry; Kingcombe; Purbeck Heaths; and Valley of the Stones. In total they cover 3.6% of the National Landscape.

• 75 Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSIs), of national importance for their wildlife and/or geological interest, which cover 10.9% of the National Landscape.

• 679 Sites of Nature Conservation Interest (SNCIs), which cover 5.8% of the National Landscape.

• 1,581 hectares of Ancient Semi-Natural Woodland and 1,485 hectares of Plantation on Ancient Woodland. Combined they cover 3,066 hectares and 2.7% of the National Landscape.

• Seven Local Nature Reserves (LNRs) covering less than 1% of the National Landscape. These are for people and wildlife, their designation reflecting the special value of wildlife and greenspaces to a local community: Asker’s Meadow; Bothenhampton; Crookhill Brickpit; Hilfield Hill; Jellyfields; Peveril Point and the Downs; and Woolland Hill

The National Landscape includes 25 of the 65 England Priority Terrestrial and Maritime Habitats, along with 281 of the 639 Priority Species, including early gentian, southern damselfly, Bechstein’s bat, marsh fritillary, sand lizard and nightjar. The majority of the land-based habitats are under agricultural or forestry management and in private ownership.

Much of the biodiversity is linked to a range of habitats across the National Landscape, which, whilst previously much more extensive, remain as a core of high biodiversity and the basis of a functioning ecological network. Strengthening the network will enable the landscape to tolerate environmental change and will also greatly contribute to the aesthetic quality. Hedges, stone walls, streams, ancient trees, copses, rough grassland, scrub, small quarries, ponds, fallow fields and uncultivated margins; all these are valuable assets to the National Landscape’s biodiversity, landscape character and cultural heritage.

The Dorset National Landscape boasts an unrivalled expression of the interaction of geology, human influence and natural processes in the landscape.

In particular, the Dorset National Landscape has an exceptional undeveloped coastline, renowned for its spectacular scenery, geological and ecological interest and unique coastal features including Chesil Beach and the Fleet Lagoon, Lulworth Cove and the Fossil Forest, Durdle Door and Old Harry Rocks. The unique sequential nature of the rock formations along the Dorset and East Devon’s Jurassic Coast tells the story of 185 million years of earth history. The significance and value of this to our understanding of evolution is reflected in the designation of the coast as a World Heritage Site. The dynamic nature of the coast means that it is constantly changing and new geological discoveries are constantly being made, emphasising the importance of natural coastal processes.

With relatively little large-scale development, the Dorset National Landscape retains a strong sense of continuity with the past, supporting a rich historic and built heritage. This is expressed throughout the landscape, as generations have successively shaped the area. It can be seen in field and settlement patterns and their associated hedges, banks and stone walls, the wealth of listed historic buildings and the multitude of archaeological sites and features. The South Dorset Ridgeway is a fine example of this, with a concentration of prehistoric barrows and henges to rival that at Stonehenge and Avebury giving a focus to this ancient landscape.

Industrial activity has also left its mark. Examples of our industrial heritage include traditional stone quarrying in Purbeck, and the thousand-year-old rope industry around Bridport which have shaped the landscape, local architecture and town design.

Geodiversity can be defined as the variety of geological processes that make and move those landscapes, rocks, minerals, fossils and soils which provide the framework for life on Earth.

The geology of the Dorset National Landscape spans some 200 million years of Earth history. Much of West Dorset is formed from Jurassic sediments that record changing marine conditions and contain an exceptional fossil record. Cretaceous chalk and sands lie across the central swathe of the National Landscape covering the Jurassic beds. In the east more recent deposits from the Cenozoic – sands, gravels and clays – overlie the Cretaceous rocks, giving rise to important heathland habitats. In addition to the geology and fossils, the Dorset coast is renowned for its geomorphology and active erosion processes. Key sites and features include Chesil Beach, one of the world’s finest barrier beaches; West Dorset’s coastal landslides; Horn Park Quarry National Nature Reserve; the fossil forest and dinosaur footprints in Purbeck and the Weymouth anticline and the Purbeck monocline structures. Significant collections at Dorset County Museum, Etches Collection Museum, Lyme Regis Museum and the Charmouth Heritage Centre enable access and understanding.

Many of the rocks and mineral resources are important for the extraction industries; the variety of building stones found in the National Landscape is a major contributor to the local distinctiveness of our settlements.

Geodiversity underpins the natural beauty for which the National Landscape is designated. The diverse underlying geology and geological/ geomorphological (i.e. landform-related) processes are intrinsic to ecosystem service delivery, influencing soils and hydrology, wildlife habitats, landform, land use and architecture that make up the character and distinctiveness of the landscape. Dorset has an extremely rich geodiversity, most notably recognised through the designation of the coast as part of England’s first natural World Heritage Site (WHS). The Dorset and East Devon Coast WHS was selected for its unique exposure of a sequential record through Triassic, Jurassic and Cretaceous periods; this diversity is reflected throughout the Dorset National Landscape. The network of inland geological and geomorphological sites represents a valuable but less well-known scientific record of the geology and environmental history of the area and often link to the local stone industry.

Geodiversity contributes to the cultural life of the National Landscape: the Jurassic Coast is a key part of the National Landscape’s ‘living textbook’ special quality, and the qualities of stone for building have long influenced the area’s villages, towns and field boundaries.

The National Landscape includes approximately 120 miles of coastline, much of which is covered by nature conservation designations. Key marine habitats in the National Landscape are at Chesil Beach and the Fleet, which is the UK’s largest tidal lagoon and a marine Special Area of Conservation (SAC); Poole Harbour, the UK’s largest lowland natural harbour and a Special Protection Area (SPA) for birds; the coast in Purbeck, which is protected as an SPA for its internationally important tern populations; the subtidal rocky reefs adjacent to the coast between Swanage and Portland, and along the Lyme Bay coast, both of which have been designated as Marine SACs; and Kimmeridge where there is a voluntary marine reserve. s. Many important wildlife species depend on both marine and terrestrial habitats for their survival, emphasising the need for integrated management.

Being a coastal National Landscape, Dorset also supports a range of maritime industries and a rich coastal and marine heritage. The main ports along the coast are at Poole and Portland, both just outside the National Landscape boundary. Fishing harbours and anchorages that support the inshore fishing community are located at Lyme, West Bay, Weymouth, Lulworth, Kimmeridge and Chapman’s Pool. Coastal resorts provide a link between land and sea where people live, come to visit and carry out the increasing trend of water-based recreation. The South West Coast Path National Trail and King Charles III England Coast Path are significant recreational resources.

The National Landscape’s coastline also has significant marine archaeology (see 5.3.3).

There are unique qualities and challenges associated with the coast and marine environments and activities both within and integrally linked to the Dorset National Landscape. While there is considerable cross over with other special qualities in relation to wildlife, geodiversity, heritage, access and local products, the nature of the National Landscape’s coast merits a specific consideration.

The coast and marine environments of the National Landscape are among its most popular and defining characteristics. Our unique World Heritage Site is globally significant, but also one of the most dynamic and changing parts of the National Landscape. Over half of Poole Harbour lies within the National Landscape boundary and habitats along the coast are particularly special due to the maritime influence.

Much of the coastline is within the Dorset and East Devon World Heritage Site; the National Landscape designation provides the statutory landscape protection for its setting and presentation. There are also two Heritage Coasts within the National Landscape – West Dorset and Purbeck. Heritage Coasts are stretches of largely undeveloped coastline of exceptional or very good scenic quality. While not a statutory designation, they are a material consideration in planning terms and are defined with the aim of protecting their special qualities from development and other pressures. Their statutory protection is delivered through the National Landscape designation where they overlap.

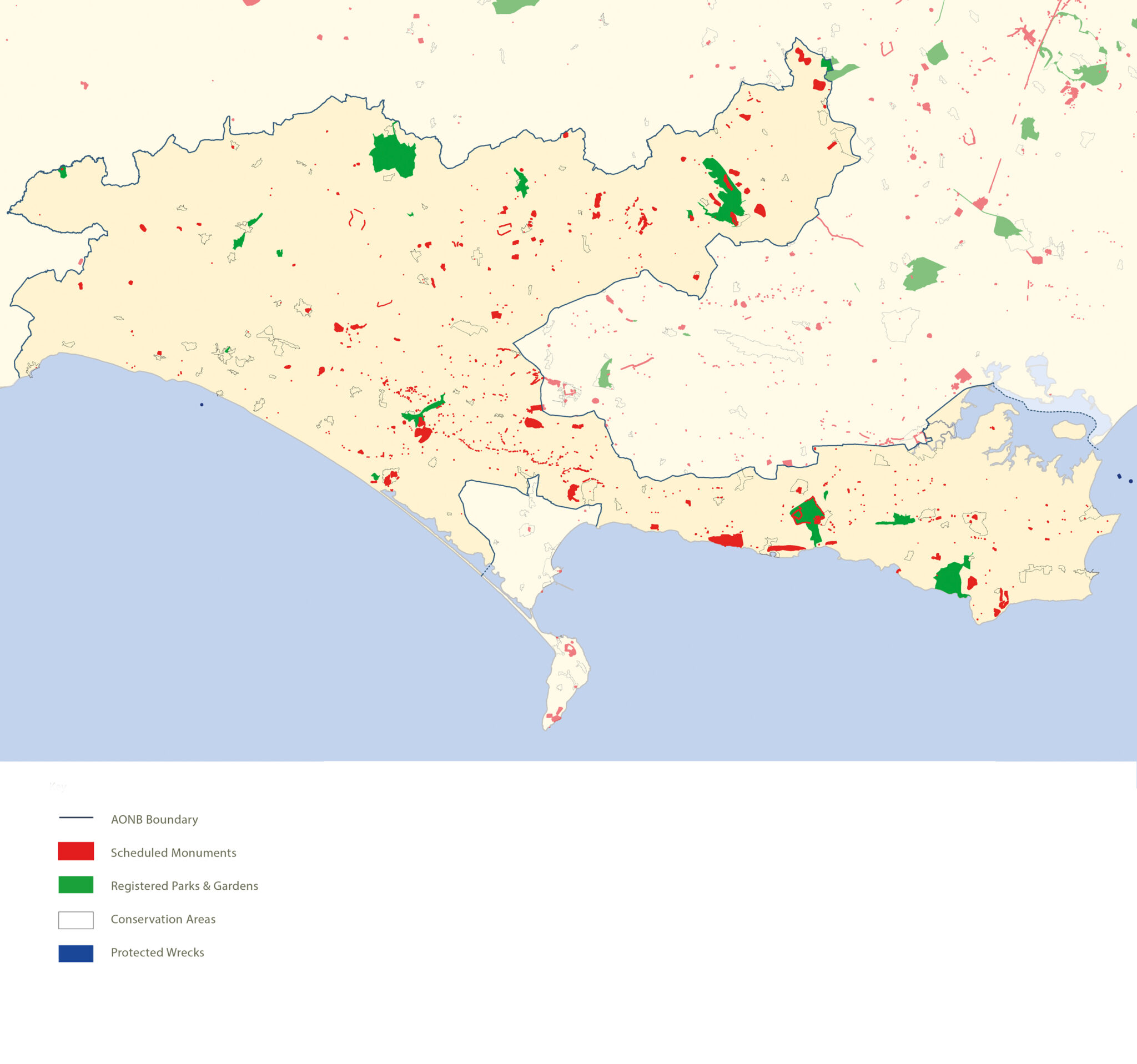

The Dorset National Landscape has an exceptional wealth of heritage, in particular nationally important prehistoric features that reveal the evolution of the landscape and human history during this period. Its transport, settlement patterns and administrative boundaries have Roman and Saxon origins and its villages and hamlets contain fine historic churches and houses. Underpinned by a complex and diverse geology, the National Landscape contains a wealth of traditional building materials that have helped develop a unique sense of place and time depth to our villages and towns. The settlement patterns are constrained by the surrounding landscape and, along with a range of rural industries such as coppicing and water meadows, have further strengthened the sense of place.

The Dorset National Landscape boasts some of the finest visible archaeological remains in the country, such as Maiden Castle and the extensive Neolithic / Bronze Age ceremonial landscape of the South Dorset Ridgeway. Significant features span all ages, from the Neolithic to the present day, and are visible in the National Landscape’s landscape; there is even some evidence of earlier human activity.

The Dorset National Landscape has 542 Scheduled Monuments totalling over 1,150 ha. Also within the National Landscape are 19 registered parks and gardens covering over 2,500 ha (1 Grade I, 9 Grade II*, 9 Grade II), 17 locally important parks and gardens, 89 conservation areas, and 4,009 listed buildings (114 Grade I, 223 Grade II*, 3,672 Grade II).

The Dorset National Landscape also has one of the highest proportions of listed buildings in the country, many of which are thatched, lending a local distinctiveness to most of its settlements. Offshore, there are over 1,700 reported shipwrecks between Lyme Regis and the mouth of Poole Harbour, 270 of which have been located on the seabed. Of these, seven are protected wrecks (of only 57 such sites in English waters) and there are six sites designated under the Protection of Military Remains Act (of only 54 such sites in British waters).

Archaeology is under-recorded in the National Landscape, both for specific features, such as historic agricultural buildings and rural industries, and geographically, such as the vales in the west of the area. Woodland archaeology is also under-recorded, both in terms of archaeology beneath woodlands which is hard to survey and archaeology relating to past woodland management, such as sawpits and wood banks.

Significant archaeological collections at the Dorset Museum & Art Gallery, Wareham and Bridport Museums enable access and understanding. In addition, Poole and Portland museums house important maritime collections.

The marks of human occupation are integral components of the ‘natural’ landscape; a record of how people have used the environment and the resources it provides over time. Alongside giving an insight into the lives of previous occupiers of the landscape, they provide a sense of time depth and contribute to uniqueness in a sense of place.

Over the centuries, Dorset’s landscapes have inspired poets, authors, scientists and artists, many of whom have left a rich legacy of cultural associations. The best known of these is Thomas Hardy whose wonderfully evocative descriptions bring an extra dimension and depth of understanding to our appreciation of the Dorset landscape. Other literary figures inspired by Dorset’s landscapes include William Barnes, Jane Austen, John Fowles and Kenneth Allsop. Turner, Constable and Paul Nash are just a few of the many artists associated with Dorset, while Gustav Holst captured the character of the Dorset heathlands in his work ‘Egdon Heath’. Such cultural associations past, present and future, offer a source of inspiration to us all and may help develop new ways of understanding and managing the National Landscape.

Dorset National Landscape’s landscape quality has inspired numerous renowned visual artists who lived or visited the area in the past. It was in the 19th century with new connections by rail that Dorset began to attract a wealth of artistic talent with JMW Turner and John Constable visiting. Into the 20th century Paul Nash and members of the Bloomsbury group were amongst those producing an abundance of work during this time. There remains a strong body of visual art representing the landscape; the distinctive topography and structure of the landscape unifying very diverse styles of representation as it did with past artists.

There is also a rich heritage of writing inspired by the landscape. Perhaps the best known is the work of Thomas Hardy, who embedded the landscape deeply in his work not only depicting its qualities but also how it shaped the lives of people who lived here. Reverend William Barnes also captured the essence of the Dorset landscape and dialect in his works, as well as the traditions of rural life. Other writers include Jane Austin, Daniel Defoe, John Fowles and Kenneth Allsop. The writing of Sylvia Townsend Warner and Valentine Ackland was rooted in the Dorset landscape and offers spectacular insights into LGBTQ+ lives from the 1920s to the 1970s.

There is a significant literature collection at Dorset Museum & Art Gallery.

Musical inspiration can be heard in the work of Gustav Holst in his Egdon Heath work and music was a central part of rural life – Thomas Hardy took part in the West Gallery musical tradition here. Materials from the National Landscape have made a significant contribution to artistic work around the world. For example, Purbeck stone was crafted into celebrated decorative work in St Paul’s Cathedral and Blenheim Palace by Sir James Thornhill. High profile architectural advances continue at Hooke Park promote contemporary use of natural materials derived from the National Landscape.

The Dorset landscape continues to attract artists, writers and musicians to visit and live, with over 3% employment in the creative industries in Dorset. The landscape provides inspiration and a backdrop for renowned artists and cultural organisations including PJ Harvey, Cape Farewell, Common Ground and John Makepeace. Over 600 artists open their studios during Dorset Art Weeks with Purbeck Art Weeks and other open studio events also very popular. There are also five National Portfolio Organisations funded by the Arts Council in Dorset (Activate Performing Arts, Artsreach, Bridport Art Centre, B-Side, Diverse City); five based in Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole and two based close to the north at Yeovil. These form a supportive backbone for arts development and strive to provide a rich cultural programme for people who live, work and visit the National Landscape.

The rich legacy of landscape-inspired work by writers, artists and musicians of the past has been recognised as one of the special qualities of the Dorset National Landscape. The work created by these nationally and internationally renowned figures not only depict landscapes of the past but help us understand more about how people lived and how both landscape and lives have changed over time.

Artistic responses to landscape also help us interact with and be sensitive towards natural beauty in ways which scientific, reductive approaches cannot. It is essential that this experiential element of landscape is recognised, and access to it is enhanced for the benefits it can bring to people’s lives. The creative exploration of place, through music, painting, written and spoken word, and dance opens up the experience of landscape beyond the world of science and policy and helps us better understand our place in the world. With better understanding comes better choices and better stewardship; the basis of a more sustainable future.